Comment on this article

Object Lesson

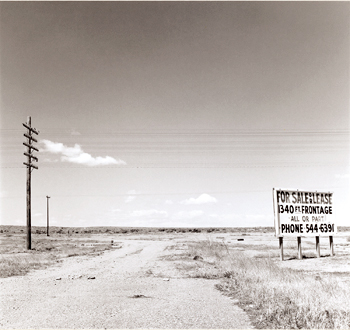

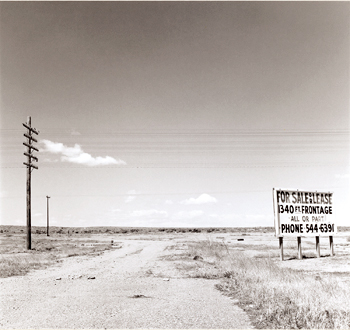

Robert Adams’s “Along Interstate 25”

November/December 2004

Architecture and American studies professor Dolores Hayden just published A Field Guide to Sprawl. Robert Adams recently donated 1,600 of his images, including this one, to the University Art Gallery.

This is the birth of sprawl.

Robert Adams took this photo in Colorado in the early 1970s. You might think that no one would want to build in this barren place near I-25. Real estate developers would call this an alligator, an investment that produces negative cash flow. But Interstate 25 runs north-south through the Denver metropolitan area, which today is a good example of sprawl—defined as careless and unsustainable use of land.

Adams photographed many components of sprawl: leapfrog development, strips, pods of tract housing, and litter on a stick (billboards). Since he was interested in creating elegant formal compositions, he tended to emphasize the play of light. He also liked to set unattractive buildings against beautiful vistas. The mood of his pictures hints that all is not well, and Adams wrote that he feared what might come next in Colorado. But any cautionary note is expressed as a kind of irony. As a result, it can be hard to understand why the land-use practices Adams depicted were so damaging.

In aerial photographs where buildings and landscapes are photographed together at oblique angles, the problems become more obvious. One can identify highways, arterials, and big box stores surrounded by enough asphalt to cover ten football fields. One can illustrate a car glut or a mall glut as part of a larger discussion about tax policies that have favored accelerated depreciation for greenfield commercial real estate. Perhaps Adams had a more poetic point of view—he worried about the year 2004 but left it to the viewer’s imagination.

Light of Heart

Anthony Weiss ’02 teaches and writes in New York.

On a late-summer evening in downtown New Haven, I was watching a light sculpture next to the Yale Repertory Theatre when a homeless man came over to join me. He had seen the sculpture before, but he was back for another viewing. “It catches your eye, and you come over to stand and watch what it does next,” he said.

We sat in silence. The sculpture, Chasing Rainbows/New Haven, was indeed eye-catching—a large, rectangular bank of 20 light tubes, across which a series of patterns cycled, melding into one another: large, geometric blocks of color; small pixels skittering across the screen and colliding with each other; vivid cascades streaming down like water. “Look at it!” said Gary, the homeless man. “There’s no way you can keep up with these patterns. There’s too many.” He was quiet for a moment. “I’d like to ask the guy that made this, ‘What were you thinking when you invented this?’ Was he in another world?”

A few days later, the guy who made it welcomes me into his studio in New York. “Sorry, this place looks like a bomb just hit,” says Leo Villareal ’90. He is dressed in shorts and a polo shirt, he is sweaty, and he looks to be very much of this world. The studio is large, but utterly cluttered, with light fixtures, open cardboard boxes stuffed with electrical supplies, several enormous brown beanbags, coils of electrical wire. A sculpture sits on a chair—a white box, one foot square, covered with white light-emitting diodes (LEDs) that wink on and off in rapid succession.

Villareal has spent the past several years designing high-tech light sculptures. His work explores patterns that change over time, repeating, deteriorating, and evolving in almost organic fashion. He is particularly interested in simple rules that create complex behavior. The patterns of Chasing Rainbows/New Haven are inspired in part by the Game of Life, a matrix sequence devised by mathematician John Conway to demonstrate the inevitability of living organisms in the universe. In the game, points on a matrix turn on or off according to how many of their neighbors are on or off.

Though his work is technically rigorous and often scientifically inspired, Villareal likens his creative process more to that of a composer than a scientist -- creating backgrounds and foregrounds, solos and harmonies. His light shows have been used by musicians, including Moby, and he will be one of the youngest artists featured in “Visual Music: 1905–2005,” an upcoming exhibit at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and the Hirshhorn Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Chasing Rainbows/New Haven was commissioned by Site Projects, a New Haven arts organization, and displayed this summer during the city’s annual International Festival of Arts and Ideas. Villareal notes that New Haven has changed a great deal since his days as a sculpture major at Yale. “New Haven at that point was sort of an industrial wasteland. There was weird stuff lying around everywhere.” He gathered these found objects—old lighting, pieces of machinery—to make his sculptures.

Villareal produced his first light sculpture in 1997, using 16 strobe lights, and his work has steadily grown more complex. His pieces now use LEDs that can create more than 16 million colors and change up to 50 times per second. He speaks of light with an almost mystical reverence. “Light affects us very deeply,” he says. “It’s not verbal, it’s very old. Like flickering fire.” He is often surprised at the effects his public works have. He visited Chasing Rainbows/New Haven where it was first installed, on the Green, and found people picnicking in front of it—“sort of a weird techno-campfire thing.”

Susan Smith, one of the picnickers and a member of Site Projects, offered me her own story. “One night, a group of young boys were riding bikes, and one of them came over and said, ‘What is that?’ I said, ‘It’s a piece of light sculpture,’ and he turned back to his friends and he yelled, ‘It’s art!’”

A-B-C, Easy as P-h-D

Christopher Arnott writes about music and theater for the New Haven Advocate.

Is Michael Jackson impersonating himself?

What if Michael Jackson were a homeless person in Washington Square Park?

When considering the liminality and multiple personae inherent in Annie Leibowitz’s photographic portrait of the “Man in a Mirror” singer literally standing amidst a bunch of mirrors, how can we miss the significance of the tain of the mirror?

These and other academic koans were debated, if not quite answered, at a scholarly conference in September titled “Regarding Michael Jackson: Performing Racial, Gender, and Sexual Difference Center Stage.” The conference, organized by visiting professor Seth Clark Silberman and graduate student Uri McMillan, was sponsored by Yale’s Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies and the African American Studies department. It sought to give the embattled yet oddly beloved pop icon the academic scrutiny his life and work deserve.

Given that he is an alleged child molester who has always evaded questions regarding his rumored homo- or bi-sexuality, Jackson might seem an awkward choice for scholarly discussion in a Queer Studies forum. But Silberman says he and McMillan understood these concerns and made them integral to the event by scheduling such talks as “Michael as Monster” and “The Uses of Child Abuse.”

The presenters, mostly graduate students and recent PhDs, came from a range of fields, including music, English, economics, and American, African American, and women’s studies. Only one of the 15 speakers had direct ties to Jackson: Todd Gray, the King of Pop’s personal photographer from 1979 to 1983. In a presentation of work from the period, Gray (now a professor of photography at California State University–Long Beach) said he’d been told by Jackson’s handlers to take more “masculine” photos in order to deflect rumors that the singer was gay. By way of contrast, he showed the photos Jackson himself enjoyed and encouraged: shots of him kissing a kitten, or chatting with Mickey Mouse. Gray’s firsthand knowledge of Jackson often lent some concrete reality to the proceedings. At a panel analyzing differences between the Never-Neverland of Peter Pan and Jackson’s real-life Neverland Valley Ranch, Gray offered that J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan was one of the two books Jackson admired most. (The other: Og Mandino’s Greatest Salesman in the World.)

Despite the free admission, international media attention, and universally popular subject matter, the audience consisted almost entirely of scholars, who sat grave and focused through the lectures. No one tittered, for instance, when McMillan mentioned that a certain topic was “germane” to a discussion of Jackson. Were there no specialists on Michael’s brother Jermaine in the house?

After the final panel, the crowd shifted rooms, and shifted gears, for a performance by Lyle Ashton Harris, an artist noted in the New York art world for his highly physical explorations of gender and sexuality. Harris evoked Jackson’s obsessions with childhood and skin color by clambering around the Harkness Hall classroom wearing a makeshift diaper that barely stayed on his painted body. An endless loop of Jackson’s ode to a rat, “Ben,” played in the background, while slides spanning his many lives and surgeries were projected on a screen. Harris cavorted about the small, packed room for half an hour, until he finally ended the ordeal by tossing a large baby carriage out the back door of the room—over the heads of visibly terrified academics seated in the last row. Then he vanished.

After a pause, he reemerged, cheery and upright, strolled to the front of the room, and friskily inquired “So! How was the conference? Any questions?”

None that another dozen gender studies and pop culture conferences can’t resolve.

Becoming Minimal

Better Off: Flipping the Switch on Technology

by Eric Brende ’84

HarperCollins, $24.95

Reviewed by Glenn Fleishman ’90

Glenn Fleishman writes books and magazine articles about technology.

Certain movies make you shout out, even though you know better, “Don’t go into the basement! Don’t answer that phone! Don’t get on that bus!” Eric Brende’s book Better Off makes me want to cry, “Get out of the way of your own story!”

Brende takes his academic study of modern technology—that is, of whether modern technology works for its owner or makes its owner work for it—to its natural conclusion in the field, by joining an Amish-like farm community in the Midwest. But it takes him a good half of the book to stop pontificating and tell what becomes an engaging story.

The book opens with and quickly dispatches Brende’s motivation and education, which led him after his undergraduate stint (Yale’s name shyly missing from this part of the text) to the heart of his darkness: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In a program called Science, Technology, and Society, designed to study “the social effects of machines on human life,” he finds his calling.

As he nears the end of his master’s degree studies, a chance encounter on a bus with a man he thinks is Amish leads him to a quiet community in an unnamed town. Brende, who wants to protect his subjects, dubs Amish, Mennonite, and simple-life adherents “Minimites” because they eschew powered motors and electricity. (I place his Minimite community somewhere in southern Indiana or Illinois.)

Brende fully disclosed his intent before one couple agreed to rent them a house. And the Minimites not only tolerate Eric and his wife Mary Brende, but also ease their way substantially. The couple’s neighbors and landlords quietly and determinedly impart farm and husbandry wisdom, and Brende is gradually brought into the regular work and social life of the community.

The writer makes plain that without help, he and his wife would have quickly run out of cash and food. It’s hard to know whether Brende is as hapless as he portrays himself initially: in the first few chapters, he marries a remarkable woman he barely knows, moves to a community he hasn’t visited, starts farming without any on-the-land experience, and tackles a team of horses without oversight. I won’t even mention his encounters with bulls.

This part of the book is marred by some heavy-handed parable-making and writ-large pronouncements. (“As these frugal people well knew, technology, and in particular motorized machinery, always brings a cost.”) But Brende’s charm and cleverness in describing his day-to-day life eventually take over. Near the middle of the book, he settles down to concentrate on telling his picaresque story, which actually reveals more than his intellectualization of the experience.

On his first community wheat harvesting, he starts living in his body at last: “My temples began to throb, and everything started to get blurry. Only the occasional, slight movement of air brought relief; my clothing was like a plastic bag that sealed in perspiration. The heat was like nothing I’d ever experienced. It seemed to bake me from within. One of the men turned to me: ‘How’s the “good life” treating you?’ There was a smirk on his face.” A few days of recuperation later, he’s acclimated himself to the heat and tries again. “Since my last stint it was almost as if my body had developed a craving for work. Odd, that pain could feel almost… good [ellipsis his]. ‘Yeah, we remember,’ guffawed Gideon. ‘Your face was so red, we didn’t know what to think about it.’”

Brende’s near-total idealization of the Minimite lifestyle starts to dissolve as the book progresses. Realism sets in, though not dissatisfaction. The more they are accepted, the more the Brendes recognize the differences that separate them from the Minimites. Some of the differences are religious. The Brendes are Catholic; the community, largely Anabaptist. Eric Brende ultimately winds up in a church service, alternating between listening intently and loudly snoring like the other men. The people he had put on a pedestal come to earth as his narrative progresses, and his simple life becomes more complicated—but not less happy.

Looming large in its absence is any mention of Scott and Helen Nearing’s classic Living the Good Life and related books, which documented their return to a life that would allow them self-sufficiency and the freedom for hours of contemplation every day, much as Brende pursues. The author also doesn’t fully deal with the Minimite and similar communities’ participation in the cash economy or their use of tools whose manufacture requires massive industrial infrastructure such as mining, refining, and smelting. He admires tempered steel, and he doesn’t bring the same critical awareness of its origins and influence that he does to electricity, gasoline, and motors.

Ultimately, the Brendes’ exit cue is Mary’s allergy to horse dander. It’s a perfect reason, or excuse, for them to separate from a community that’s close to what they wanted but not perfect, and try to develop their own way in the world, closer to their urban roots. They now live in St. Louis, where Eric drives a bicycle rickshaw and makes soap.

Brende doesn’t ever really admit that living as lightly as he did requires a busier economy around him, but he paints a lovely picture of a quieter, more contemplative life. For neo-back-to-the-landers, Better Off should become required reading for its insight and good nature.

A Life with Yale

A Life with History

by John Morton Blum

University Press of Kansas, $35

Reviewed by Bruce Fellman

Bruce Fellman is managing editor of this magazine.

In late April 1957, a 36-year-old MIT historian named John Morton Blum was ushered into the office of George Wilson Pierson ’26, chair of Yale’s prestigious history department. Earlier that month Pierson had written to Blum to ask him to join the department. Blum promptly accepted, but when he visited to work out the details, he received a chilly greeting:

“There he sat, patrician arms folded across his patrician chest, patrician nose in the air, welcoming me with a question: ‘What business have you at your age looking at a Yale professorship?’

“Stunned, I replied rather slowly, ‘Why, Mr. Pierson, you offered me one.’”

Yale was a different place back then—an institution still enmeshed in WASP traditions, one of which was lingering anti-Semitism (Blum was a non-observant Jew). It was also distinctly clubby and conservative. In a book rich with detail and filled with insightful portraits of Yale greats, Blum recounts his life as soldier, scholar, administrator, first Jewish fellow of the Harvard Corporation, and all-around opinionated gadfly. He was once accused of being a Communist by Yale historian Samuel Bemis. The undergraduate guide to Yale courses carried this comment: “Blum—biased about everything.” (Nevertheless, his courses were extremely popular. “You have to take Blum” was the word on campus for decades.) Throughout, the Sterling Professor Emeritus who explored the lives and impacts of Woodrow Wilson, Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt, and others offers a fascinating history of Yale during a time of rapid and significant change.

A Legitimate Artist

John James Audubon: The Making of an American

by Richard Rhodes ’59

Alfred A. Knopf, $30

Reviewed by David Baron ’86

David Baron is the author of The Beast in the Garden (Norton, 2003).

In March 2000, a sale at Christie’s New York set a world auction record for a printed book. The price: $8.8 million. The item that fetched this lofty sum was The Birds of America, a four-volume, leather-bound collection of hand-colored prints by the artist John James Audubon.

That a century and a half after his death Audubon retains such enthusiastic admirers says much, and not only about his artistic talents. The man has become an American icon. Audubon’s name adorns parks and country clubs, a peak in the Rockies, a zoo in New Orleans, and a national environmental organization that boasts more than half a million members. In twenty-first-century America, the nineteenth-century naturalist has come to symbolize the lost, pristine beauty of this nation’s past—its birds, wildlife, wilderness.

And yet, as Richard Rhodes demonstrates in his engaging new biography, the artist-ornithologist was not as American as he often claimed to be. Audubon, who sold himself in Europe as a Louisiana-born American woodsman, was in reality the bastard son of a French sea captain. Born in Haiti and raised in France, Audubon did not come to the United States until age 18, when he fled conscription by Napoleon’s army.

The young Frenchman, handsome and athletic, settled in Pennsylvania and soon moved to Kentucky to become a frontier merchant. Early on, he displayed three passions that would drive his life: an obsession with birds, an infatuation with Lucy Bakewell (who would become his wife, in a marriage that lasted 43 years), and a pronounced love of self. Audubon, as portrayed by Rhodes, was guilelessly vain. Though insecure about his poor pedigree and lack of formal education, he possessed a deep-seated belief in his abilities and ideas.

When his business, a log-cabin general store on the Ohio River, went bankrupt in the Panic of 1819, Audubon had the pick-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps gumption to start over as an artist. The conventions of the day saw natural history illustration as a dry, scientific endeavor, but Audubon reinvented the painting of birds as an artistic enterprise; he depicted turkeys and flycatchers, eagles and larks life-sized, in animated poses and natural settings, and often from a bird’s point of view. With no guarantee that his hard work would pay, he sailed to England, secured a publisher, and scoured Europe and America for wealthy subscribers who signed up to receive The Birds of America in installments. (The 435 prints would be produced and distributed over a 13-year span.)

The story is a surprisingly triumphal one for Rhodes, who received a Pulitzer Prize in 1988 for The Making of the Atomic Bomb and whose best-known other works explore similarly bleak topics: mad cow disease, the origins of criminal behavior, the author’s own childhood of abuse. Audubon’s was “a staggering achievement,” writes Rhodes, “as if one man had single-handedly financed and built an Egyptian pyramid.”

At its best, Rhodes’s biography is both movingly intimate and grand in scope. The author quotes liberally from Audubon’s letters and journals, and he adds rich digressions on American history and the perils of frontier life. Audubon contracts yellow fever, sinks in quicksand, gets iced in on a Mississippi flatboat, endures swarms of buffalo gnats so thick they could—and do—kill a horse (his). Yet the frontier also provides unparalleled freedom, allowing a man to rise above his shameful birth and invent a new persona. Rhodes portrays the parallel development of the young artist and his young, adopted nation. “Individualism was not a feature of the American national character imported from Europe,” Rhodes writes. “It emerged and evolved in response to the conditions of continental settlement, and the era of its emergence coincided with the evolving lives of John James and Lucy Audubon.”

Later chapters, which follow Audubon to England, unfortunately lose this thematic thread; they are most memorable for the poignant letters between Audubon and his wife, who during a three-year trans-Atlantic separation communicated by the frustratingly unreliable mail system of the day. But throughout, Rhodes’s is a vivid portrait of an exceptional life. Part Davy Crockett, part Henry Thoreau, and part Donald Trump, John James Audubon was not just a great outdoorsman and artist; he was an indefatigable salesman. In this way—perhaps even more so than in the subject matter of his famous drawings—the Haitian-born son of a French sea captain was, indeed, a true American.

In Print

Servants of the Fish: A Portrait of Newfoundland after the Great Cod Collapse

Myron Arms ’63, ’64MAT

Upper Access Books, $24.95

In 1998, environmentalist Myron Arms maneuvered his sailboat Brendan’s Isle around Newfoundland to investigate the cause and impact of the disappearance of the cod. His report is a cautionary tale about “the difficult choices we all face” in trying to live sustainably on a “planet that is fragile and finite and surprisingly small.”

Bad for Us: The Lure of Self-Harm

John Portmann ’85

Beacon Press, $25

“We know the rules. We sometimes disobey them anyway,” notes Portmann, a University of Virginia religious studies professor. With references along the way to everything from Immanuel Kant to the Victoria’s Secret catalog, the author grapples with the causes and consequences to ourselves of dropping self-control and indulging in a variety of sins.

The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art

Mark Rothko ’25, edited by Christopher Rothko ’85

Yale University Press, $25

Mark Rothko, said his son Christopher, was “explicitly a painter of ideas.” In the early 1940s, the painter summarized his views about the artistic process and its practitioners, but the legendary manuscript was “lost” for more than half a century. Rothko’s insights are now available for a new generation.

On Call: A Doctor’s Days and Nights in Residency

Emily R. Transue ’92

St. Martin’s Press, $23.95

“I had woken up that morning having never seen a death, and by lunchtime I had been part of one.” So begins a well-crafted collection of moving essays about what a young doctor learned about human chemistry from patients and fellow doctors during her medical education.

More Books by Yale Authors

Bruce Ackerman 1967LLB, Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science, and James Fishkin 1970, 1975PhD

Deliberation Day

Yale University Press, $30

Carol J. Adams 1976MDiv

Prayers for Animals

Continuum, $14.95

Nancy K. Anderson 1994PhD, Writer and Translator

The Word that Causes Death’s Defeat: Poems of Memory, by Anna Akhmatova

Yale University Press, $30

Harold Bloom 1956PhD, Sterling Professor of the Humanities and English

Where Shall Wisdom Be Found?

Riverhead Books, $24.95

Jacqueline Byrne 1984 and Michael Ashley

SAT Vocabulary Express: Word Puzzles Designed to Decode the New SAT

McGraw-Hill, $12.95

Stephanie M. H. Camp 1992MA

Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South

University of North Carolina Press, $39.95

Thurston Clarke 1968

Ask Not: The Inauguration of John F. Kennedy and the Speech That Changed America

Henry Holt, $25

Barbara Flanagan 1977MArch

The Houseboat Book

Rizzoli/Universe, $45

Robert Gandossy 1984PhD, Editor

Leadership and Governance from the Inside Out

John Wiley and Sons, $34.95

Paul Goldberger 1972

Up from Zero: Politics, Architecture, and the Rebuilding of New York

Random House, $24.95

Eric Goodman 1975

Child of My Right Hand

Sourcebooks Landmark, $14

Erwin Hauer, Professor Emeritus of Art (Sculpture)

Continua: Architectural Screens and Walls

Princeton Architectural Press, $35

Gary Iseminger 1961PhD

The Aesthetic Function of Art

Cornell University Press, $32.50

Bruce Judson 1984JD, 1984MBA, Postdoctoral Associate, School of Management

Go It Alone: The Secret to Building a Successful Business On Your Own

HarperBusiness, $23.95

B. Cory Kilvert Jr. 1953

Echoes of Armageddon, 1914–1918

Author House, $15

Michael Leahy 1975

When Nothing Else Matters: Michael Jordan’s Last Comeback

Simon and Schuster, $26

James Lilley 1951

China Hands: Nine Decades of Adventure, Espionage, and Diplomacy in Asia

PublicAffairs, $30

Lisa Lubasch 1995

T

o Tell the Lamp: Poemsasch 1995

Avec Books, $14

Bill McGaughey 1964

On the Ballot in Louisiana: Running for President to Fight National Decay

Thistlerose Publications, $16.95

Carol Thomas Neely 1969PhD

Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture

Cornell University Press, $52.50

Peter Perret 1960

A Well-Tempered Mind

Dana Press, $22.95

Deborah L. Rhode 1974, 1977JD

Access to Justice

Oxford University Press, $29.95

Alan F. Segal 1975PhD

Life After Death: A History of the Afterlife in Western Religion

Doubleday, $37.50

Lenore Skenazy 1991 and John Boswell

The Dysfunctional Family Christmas Songbook

Broadway Books/Doubleday, $9.95

Kimberly A. Smith 1998PhD

Between Ruin and Renewal: Egon Schiele’s Landscapes

Yale University Press, $50

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, Associate Dean for Executive Education, School of Management, Editor

Leadership and Governance from the Inside Out

John Wiley and Sons, $34.95

Howard M. Spiro, Professor of Medicine Emeritus

The Optimist: Meditations on Medicine

Science and Medicine, $32

Steve J. Stern 1979PhD

Remembering Pinochet’s Chile: On the Eve of London 1998

Duke University Press, $29.95

Lawrence Strauss 1972PhD

Opera and Modern Culture: Wagner and Strauss

University of California Press, $39.95

Jonathan Swinchatt 1957BS and David G. Howell

The Winemaker’s Dance: Exploring Terroir in the Napa Valley

University of California Press, $34.95

Strobe Talbott 1968

Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy, and the Bomb

Brookings Institution Press, $27.95

Jose Manuel Tesoro 1994

The Invisible Palace: The True Story of a Journalist’s Murder in Java

Equinox Publishing, $14.95

Harold H. Tittmann Jr. 1916, and Harold H. Tittmann III 1951, Editor

Inside the Vatican of Pius XII: The Memoir of An American Diplomat During World War II

Image Books/Doubleday, $13.95

Immanuel Wallerstein, Senior Research Scholar, Sociology

World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction

Duke University Press, $16.95

Mark S. Weiner 1998PhD

Black Trials: Citizenship from the Beginnings of Slavery to the End of Caste

Alfred A. Knopf, $26.95

Kristina Wilson 1993, 2001PhD

Livable Modernism: Interior Decorating and Design During the Great Depression

Yale University Press, $45

William Wise 1945

Christopher Mouse: The Tale of a Small Traveler

Bloomsbury, $15.95

David Wyatt 1970

And the War Came: An Accidental Memoir

University of Wisconsin Press/Terrace Books, $26.95

Terra Ziporyn 1980, Karen J. Carlson MD, and Stephanie A. Eisenstat MD

The New Harvard Guide to Women’s Health

Harvard University Press, $24.95

Rachel Zucker 1994

The Last Clear Narrative

Wesleyan University Press, $28

|